Abstract: The aim of this paper is twofold: first, to provide evidence supporting the thesis that Kautilya was the first political economist; second, to verify that a systematic study of political economy has begun long before the ideas and works of Adam Smith. It was in the works of Kautilya (around 375 B.C.). In order to validate the aims of our study, we look for evidence in his Arthashatra of rational behaviour, self-interest motivation, and market elements of a traditional commercial society. Providing a sound interpretation of Kautilya’s main arguments, we demonstrate that his is no less a systematic study in political economy than Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. Economics is a science that tries to offer policies and practices for creating and enriching a nation’s wealth, and in that sense, the Arthashastra (literal translation being The Science of Wealth) represents the first systematic manual of political economy. The development of economics as a science must take cognition of the economic principles and ideas presented in The Arthashastra so as to reveal the true origins of economic thought and its evolution. It is only by understanding methodological problems in a historical perspective we can understand the modern methodological and conceptual issues.

Introduction

The teachings and works of Kautilya (ca. 375 B.C. /1992) [1] rightfully deserve the appellation of the ‘missing link’ in economics. Unfortunately, scholars and students of economics around the world are not familiar with his work. Lately, the modern economic theory has recognized his contribution to economic thought, but no more than the work that of an exotic ‘ancient economic novelist’ (see Waldauer, Zahka & Pal 1996, p. 101). Though Kautilya’s own contribution in terms of economic concepts and principles is large and important (as we can evaluate it in Arthashastra), orthodox economic science has considered him to have had no influence whatsoever on the development of the ‘modern’ economic thought. This is a rather confusing fact, as the range of his thinking stretches from international trade, labour, wage, price, fiscal and monetary theory to economic growth process and corporate social responsibility behaviour. Orthodox economists and supporters of Finley’s (1999) theory of ‘primitive economics’ fail to acknowledge the existence of any form of economic thought that can be found before the life and works of Adam Smith (1759, 1776). To be exact, to a certain extent, they recognize ‘some’ precursors to classical economics in the work of Aristotle, de Jean Olivi, late Scholastics and Physiocrats to Mandeville. Their placement of economics on the throne of ‘modern science’ is based on two key arguments:

(1) First, that the individuals pursuing personal interests are led by an invisible hand in their work, and

(2) Second, that the market system functions to ensure the progress of society improving its social welfare through material prosperity.

Hutcheson (2010) defines economy from the Greek words oikos (household) and nomos (complex root of the word dumb – manage, order, custom, law). According to Xenophon, Oikonomicos (450 B.C.) summarizes the knowledge of more than 2000 years. The thesis that before The Wealth of Nations markets and the economic principles were only randomly associated with economic categories such as unemployment, efficiency, inflation, and GDP—and are merely products of general knowledge or philosophical reflection—is based on the postulate that the market did not exist 3000 years ago [2]. Below, we provide evidence that the market was present and functioning very well within Kautilya’s state. The market mechanism, economic policy, and growth theory models that we find in Kautilya’s Arthashastra cannot merely be the result of a simple social practice or process; they must instead be evidence of a complex economic process and the economic analysis of that process itself.

Theory of economic growth

Kautilya’s major contribution is his theory of economic growth. His theory is elaborated in minutes—both at micro and macro level, with a significant central role for the King in promoting economic growth. His economic model can be presented as in Figure 1. Elements of Kautilya’s growth model include production of goods and services, demand for goods and services, productivity, government policy, fiscal policy, price stability and monetary policy, trade, economy, welfare, productive enterprise, productivity-linked wages, the position of women in the labour market, the role of marketing in the promotion of market activity, price stability, consumer protection division of labour, specialization etc.

Mainstream economic models of today’s complex economic processes are not better formal representations of a ‘real’ world then the model Kautilya developed some 2,400 years ago. The proof for this claim lies in his The Arthashastra and the complex model of the Indian economy that he develops. The mechanism and components of the model support the evidence that economic thought and policies in ancient economies were far more advanced than we presently acknowledge. The model that we base on the data derived and the historical facts has all the ‘causality—feedback tree’ that we can find in any ‘modern’ growth models.

Kautilya nourished a multi-dimensional growth model with several interrelated variables of interest (growth factors) and bi-directional causality. In his theory, it was no mystery why would some Empires register faster growth, and why the other would move slower. The central part of his model was agriculture and fishery— two main sectors that were generating added value and wealth for the King and the State. Mining industry was also an important source of wealth, with its four industrial levels: state monopolies (dealt with making weapons and brewing liquors), state-controlled industries (textiles, salt and jewellery), state-regulated small industries (craftsmen—goldsmiths, blacksmiths) [3] and private industry (that was free, unregulated)—potters, basket makers and others [4]. Other types of industries are not directly regarded to in Kautilya’s readings.

Figure 1 Kautilya’s economic model

Source: Author

Productivity generated through the above-mentioned economic activities is the engine of economic growth. Unlike the ‘modern’ theories of growth, Kautilya did not recognize the role of unique and separable growth generators. According to him, economic growth originates from the coordination of all economic activities within the State, which has an intelligent and fair King on the top and citizens that are well protected, respected and motivated. The sole and final goal of this type of State is people’s welfare. This was his engine of growth — the one completely different from all the past and contemporary economic growth theories, which rest on pillars of economic growth yet unidentified. Thus, productivity was an important growth source, as we recognize it today [5], but Kautilya considered it only as the starter i.e. the ignition of the whole growth model. Increased boost in productivity does start the economic growth but is energy, or precisely said, the ‘growth momentum’ which is necessary for igniting the growth engine. It comes from all the previously mentioned activities and from interrelations between people and the institutions.

Productivity is only a tool here, not the final and ultimate goal in the complex growth machinery. The State plays an important role in the model by encouraging fair trade, customer protection, harmony in profit and wages, stable fiscal policy and treasury management, stable prices and positive expectations. The State, or the King, is in charge of serving and administering this sophisticated mechanism of the economy. In fact, this is the evidence to show why, in ancient economies, household and village economy was in the centre of discussion, while the national or macro-economy as we know it today was not directly mentioned or given credit. Since we cannot trace national accounts or macroeconomic flows of any type at that time, we get a wrong impression based on this presumption. Thus, there is no reason to believe that it did not exist, as the Arthashastra in itself is solid evidence of this fact.

To Kautilya, economic growth is a multi-dimensional phenomenon that results in increased economic activity, with productivity being the ultimate source. Several instances in his text provide strong evidence that he was fully aware of the economic growth process. At the very beginning of his theory he asserts that

‘A king shall augment his power by promoting the welfare of his people; for power comes from the countryside which is the source of all economic activity: He shall build waterworks since reservoirs make water continuously available for agriculture; trade routes since they are useful for sending and receiving clandestine agents and war materials; and mines for they are a source of war materials; productive forest, elephant forest and animal herds provide various useful products and animals. He shall protect agriculture from being harassed by fines, taxes and demands for labour.’ [6]

In this paragraph, we can recognize several growth notions. Firstly, agriculture was the main source of economic growth, as it was well-known then that

‘(…) cultivable land is better than mines because mines fill only the treasury while the agricultural production fills both the treasury and storehouses.’ [7]

The Indus Valley civilization was supposed to be the most productive, capable of generating large surpluses sufficient enough to support big cities along the empire. Historically, though this fact is still under debate, Kautilya provides clear evidence when he states that the countryside is the main source of all economic activity. Moreover, a significant part of opus is devoted to the farmers and agriculture, as the central activity in the Mauryan empire (323-185 BC), and the importance of the agricultural sector to the empire is visible from the fact that all activities involving land in the empire were under the control of the Chief superintendent of the State. It was his duty to monitor all activities involving land cultivation.

Land was divided into crown land, private land and pastures. The central point of the countryside activity was the village, as a cornerstone of the village economy within the empire. Farms were agricultural areas, with a minimum of one hundred families and a maximum of five hundred families with arable fields that can be ploughed by one, two or three ploughs. [8] A similar organization agricultural activity and agronomic practices can be found in today’s agricultural household. Since the whole land was owned by the State, it was in charge of the land’s disposition. The State could grant the land to priests, preceptors, chaplains and Brahmins without taxes or fines, and without the right to sale or mortgage. Agricultural policy was set in accordance with the type of land under disposition. Non-arable lands were given to cultivators, or to slaves that were employed to work on the land.

Another important aspect in Kautilya’s theory is the idea of diversified and sustainable economic growth. Only a diversified economy can assure stable and prosperous economic growth. Private property and self-interest had a strong role in promoting personal welfare and, in turn, state development. According to Kautilya, all subjects within the Kingdom were equally important for wealth creation—from the King to the slave. The degree of responsibility was another point. While the King is considered to be responsible for the total wealth of a Kingdom the slaves were responsible for wealth creation on the piece of land they were working on. State had no priority prior to the welfare of all King’s people. State and government officials were responsible to the King and the people. They were public servants and not ‘power figures’ as today. In fact, if we look at the list of their duties and penalty fees in relation to their wages, we shall see that the State had no intention to protect or elevate them to some high-status position in the Kingdom. Their main duty was to safeguard and uphold the invisible hand, promoting material production and activities resulting from any state servant. Any government official who failed to do so was strictly punished—for levying excessive tax burden on farmers, consenting merchants to determine unfair prices, promoting monopoly behaviour on the market. Thus, The Arthashastra’s is in no sense typical state capitalism. King was not allowed to depredate households of private wealth or run commercial enterprises as he pleases in the state capitalism tradition. This is what Kautilya actually writes:

‘In the happiness of his subjects lies his happiness; in their welfare his welfare. He shall not consider as good only that which pleases him but treat as beneficial to him whatever pleases his subjects.’ [9]

From this statement we could infer that The Arthashastra presents a sum of the ‘invisible and visible hand’ system where the King (representing the State) is taking care of resource allocation (the visible hand) and listening to the needs and motives of his subjects (the invisible hand).

Theory of fiscal policy

Fiscal policy and particularly the functioning of the treasury was well organised within the ‘Treasury’ (Arthakosh). It was like the Budget under the control of the Chancellor, one among the most important officials of the Crown. Government officials stipulated standard ‘blueprints’ for how the treasury should be built in order to be safe. Budget accounts and budget policy were also well-stipulated, planned to every detail. In some aspects, they were even more detailed in comparison to the existing budget policies of modern states. However, in Kautilya’s writings, we do not find a concept of national account, even though we do find the number and the levels of accounts clearly defined and described under budget accounts.

The procedure of the budget policy, for a fiscal year with all departments (entities) included and that reports responsibility elaborated under the Chancellor’s supervision, is in no way of lower-quality in comparison with the procedure adopted in the economies all over the world today.[10] Comparisons between the budgets procedures in today’s developed economies and the budget policy procedure described in The Arthashastra provides us with striking facts about the advanced level of fiscal policy in the Mauryan State.

‘The Chancellor shall first estimate the revenue (for the year) by determining the likely revenue from each place and each sphere of activity under the different Heads of Accounts, total them up by place or activity, and then arrive at a grand total.’ [11]

Credit side of the account or the budget revenue sources included revenues from:

1) Income from Crown property

a. Crown agricultural lands (production and lease)

b. Mining and metallurgy

c. Animal husbandry

d. Irrigation works

e. Forests

2) Income from State-controlled activities

a. Manufacturing industry – textiles

b. Manufacturing/leisure industry (liquors)

c. Leisure activities (courtesans, prostitutes and entertainers)

d. Betting and gambling

3) Taxes – In cash and in kind

a. Custom duty

b. Transaction tax

c. Share of production

d. Tax in cash

e. Taxes in kind

f. Countervailing duties or taxes

g. Road toll

h. Monopoly tax

i. Royalty

j. Taxes paid in kind by villages

k. Army maintenance tax

l. Surcharges

4) Trade

a. State trading

b. Compensation payments

c. Excess value realization

5) Fees and service charges

6) Miscellaneous

7) Fines [12]

Debit, the expenditure side of the budget, was carefully elaborated equally well. However, Kautilya was against any tight fiscal policy measure recognizing the negative effects of fiscal austerity and ‘deficit fetishist’ supporters on personal consumption and in turn on the supply contraction. This is clearly implied in his remark

‘State’s Officer who procures double of the normal revenue consumes the countryside. If he brings in the whole share for the King, he should be warned in case of a minor offence; and in case of a major offence, he should be punished according to the offence. He who makes out as expenditure the revenue which he has raised, consumes the work of men; and he should be punished according to the offence in cases of loss (waste) of days of work, the price of goods and the wages of men.’ [13]

Evidently, as some believe even today, fiscal austerity is a way to economic distress, as it ruins personal wealth and power of consumption generating business cycles in the State.

Monetary policy

Money circulation in the Empire had two main functions: wealth accumulation an ‘grease’ for the trade and assertion of monetary sovereignty. A single currency was adopted across the Empire that was ensuring monetary sovereignty of the State. The danger of the inflation problem was taken care of through tough measures associated with money in circulation. It is evident from the fact that a special Coin Examiner was in charge of controlling the currency (gold standard) in the State. A severe punishment was stipulated for money counterfeiters and especially for those responsible for its circulation employed in the treasury (for them, the punishment was death). In addition, ‘(…) a lax anti-counterfeiting policy is inconsistent with price stability.’ [14]

Allowing counterfeiting and not controlling the currency in circulation, implies inflationary pressures. Monnet (2005, p.7) demonstrates that ‘if a central bank wishes to take action against this activity without increasing the cost of counterfeiting itself, it will have to inflate the stock of legitimate money. As inflation increases so the relative cost of counterfeiting, it reduces counterfeiting incentives’. From this observation, indirectly, we could infer that to Kautilya, being the chief economic policy architect, price stability was important and so was the relationship between the money supply and price stability (or inflation) within the Mauryan Empire. While controlling the money, State officials were obliged to control inflation and price stability, because according to him, mixing of the genuine coins with the false ones would result in depletion of the government’s treasury. Stock of coins in circulation in the Empire would thus outgrow the stock of goods in Government’s property, stored in commodity warehouses and granary (treasury).

Loans and deposits represented an important subject in Kautilya’s economy, because, as Kangle states, ‘the law of evidence was indeed formulated primarily in connection with debts’. [15] All contracts had to be made in the presence of witnesses and completed with all the details, including time and place. Debts between father and son, or husband and wife were not recoverable, but—in harmony with justice perceived in early India—the obligation of the debtor should not be increased if the debtor is engaged in performing rites for a longer period, if the debtor is ill, or if he is under tutelage in teacher’s house, or a minor, or even insolvent. [16]

Trade policy

Trade in ancient India was an important factor of growth. Trade routes were supposed to be established and trade markets in the cities promoted in order to generate wealth in the kingdoms. Both import and export policies were placed under the strict trade control system. Merchants, to Kautilya, were important for trade, but since they did not generate any form of material wealth, price distortions resulting from high merchants’ profit margins or due to other speculative behaviour were put under strict control (money fines and taxes). Kautilya was not concerned with the balance of payment equilibrium. Import was oriented toward wealth creation. Commodities not produced domestically or available at high prices (high costs of production) through price subsidy, as well as spot, future mechanisms were imported. Commodities eligible for import included only goods of strategic and intrinsic value. Useless goods not favouring any wealth creation were prohibited. Import had also a role of market protection. In times of shortages on the market, merchants were encouraged (by price subsidy and preference custom duties) to import more good in order to build a buffer stock. To attract more goods in the country, higher than the regular price on the market were awarded. After the buffer stock was built, excess of supply on the market was sold at a lower price so to re-gain the price equilibrium. A system of comparative advantage was used in advancing exports to regions and areas generating profits while unprofitable areas were avoided. Exception was made in the case of exporting commodities to possible future aliases or strategic trade partners. A complete system of trade tariffs, import rates, trade duties, price subsidy and trade control system was set up to facilitate and safeguard trade activities.

Export was given an important role in creating kingdom’s wealth. Trade gross margin had to cover all the costs included in the trade operation—customs duty, tax and transport charges, costs of hiring ships or boats, escort protection and associated costs. Trade operations that could not cover for the costs within the gross margin were avoided. Terms of trade had also an important role in the trade system with maximizing or minimizing (avoiding losses) the export/import price difference. Trade with higher export prices in relation to the import prices from a specific area or region was particularly stimulated. Trade officers and others government officials were in charge of safekeeping and promoting trade and establishing secure trade routes. No kingdom can survive selling domestically produced goods (from the countryside or cities) near the same market areas where the same were produced, as this would result in future losses and thus market surpluses. Strategic partners were to be attracted through bilateral agreement and two-way trade policies (comparative advantage favouring both nations).

Labour and wage theory

As stated above, Kautilya considered productivity as an important source of economic growth. Productivity, in return, according to his theory, depends on the level of the division of labour, wages, incentives and inequality. This is clearly visible from the subsequent passages, which represents the nexus between productivity and wages.

‘He, (the Superintendent of Yarns) should fix the wage after ascertaining the fineness, coarseness or medium quality of the yarn, and the largeness or smallness of quantity. Wages for the labourers in the textile industry were thus closely monitored and fixed according to the amount of output that workers could produce (productivity level). Incentives were provided for the workers, if good results in the production process were achieved.

After finding out the amount of yarn, he should favour them with oil and myrobalan unguents. And on festive days, they should be made to work by honouring them and by making gifts. In case of diminution in yarn, and according to the value of the staff, it will come to a diminution of wage.’ [17]

It seems that the Kautilyan economy was operating in accordance with the efficiency wage theories, with the State having to choose to pay wages above the average market wage, in order to increase productivity and future revenue to the State.

However, policymakers and controllers were aware that paying efficiency wage to workers could lead to an involuntary unemployment, so whenever the disequilibrium between productivity level and wage level was noticed, the wages were forced down to the productivity wage equilibrium level. Wages were paid to the workers in accordance with the theory of division of work [18] and specialization theory, as can be seen from the following quote. [19]

‘Spinning shall be carried out by women and weaving should be carried out by men (ropes, protective wear straps and similar articles shall be made by specialists in their manufacture). The Chief Commissioner shall come beforehand to an agreement with artisans regarding the amount of weaving required to be done in a given period, and regarding corresponding wages needed to be paid. Incentives shall be given to weavers of special types of fabrics, such as those made from silk, fine yarn, wool from deer, etc. ‘

Prices and market system

Kautilya’s view on the price mechanism was lot alike to classical school of economics. Forces of supply and demand were actively operating on the market under the brisk eye of the state intervention. Confronting the present market system with the one that existed in the time of Kautilya, we come down to a single crucial point—how much of the government do we need? Looking at Kautilya’s market system, we could state with great certainty that his was of a very high degree of state interventionism.

For a moment, let us turn to the current global financial crises (2008 onwards) and shed some new light on the subject. Currently, governments particularly in OECD countries around the world are taking strict and sometimes dramatic actions for handling the crises. Many measures have involved banks and firms. Nationalization measures have also been taken. We know that nationalization has long been considered, in fact, the supreme form of centralized and planned economy, yet the world economies that have implemented nationalization are considered as regular market economies. What an anomaly! There is no greater force in the domain of state intervention on the market than the nationalization. However, it will be recorded as a historical fact that nationalization in its extreme form was used in 2008 and after, from USA to Iceland and other market economies.

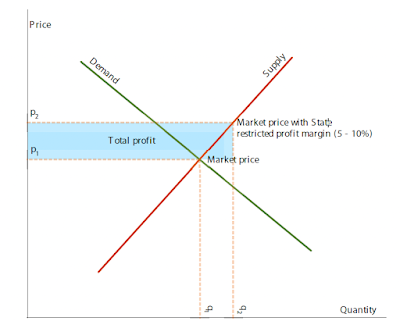

The formal distinction between market and planned economy rests on the fact that in planned economy the government sets the price of goods and services by using a fixed price mechanism. This, however, was not the case for the Kautilyan economy; the government did not use any fixed price mechanism; therefore, there does not exist a scientific reason for us not to consider the economy in question as a market economy. An alternative mechanism was used instead, and that was the mechanism of a fixed profit margin rate. Price setting mechanism in place within the Kautilya’s state is presented in the figure below.

Figure 2 Price operating mechanism in the Mauryan empire

Source: Author

As one can see from the figure, markets were operating under free market regime, but Kautilya (like Adam Smith) believed that markets produce unfair income distribution in the society. Further, Kautilya seems to have been well aware of the negative externalities inherited in tax and tax policies—higher taxes lead to lower consumption, lower personal incentives, lower production and in turn higher unemployment and economic cycles. So he had no intention to use tax policy for income (re)distribution since he thought it will generate more damage then good. His idea was to limit the profit margins on the markets and at the same time limit or completely prevent markets generating an unfair income distribution. The question remains, how will the manufacturers, entrepreneurs and traders react to such a policy mechanism? Since they were all following the idea of Dharma [20], the market mechanism was acceptable universally. It is worth mentioning that in modern ‘western’ India the same policy mechanism is no longer valid placing the country on the 79th place in the world with the Gini index at 37. Since, unfortunately, no data about income distribution (except wages across the State) can be found in The Arthashastra, we are, therefore, not in a position to evaluate the fact as to how much, ultimately, the ‘restricted profit margin policy’ had an impact on the income distribution and poverty.

Market character and consumers

Markets economics functions as a process from within the community and not outside it. Hypotheses of the absence of market within the community rather than exclusively outside (a separate institutional entity) and the thesis concerning the market behaviour solely through the mechanism of consumer votes and positivist paradigm is wrong and dangerous, and leads to a pronounced crisis and dramatic consequences for the economy and the world. Here, we dare say that the Kautilyan economy was a type of market economy, in no way different from today’s, except for a strong State intervention in the market. Accordingly, to Kautilya, market failure and government failure were conjoined twins with a common stomach. Market failure could not occur without government failure, and government failure could not take place unless there was a moral failure and poor organizational design. [21] Kautilya was of the opinion that forces of a privately guided market were an interest in itself, and the invisible hand, in turn, could not look after the public interests. Government intervention was, therefore, necessary to correct the negative public externalities on the market. The supply and demand forces were to set the price mechanism in the Empire, not the government. The government was there to control and correct it, if something ever went wrong.

A significant piece of evidence can be found in his discussion on monopoly consequences for the market and public. Private manufacturers and merchants were obliged to pay a licensing fee and in case of the state monopolized commodities paid monopoly tax. Further, another form of market externality, cartelization, was to be controlled by the State, ‘by artisans and craftsmen with the aim of lowering the quality, increasing the profits or obstructing the sale or purchase with fine of 1000 panas prescribed.’ [21]

Kautilya’s economy was a regular ‘mixed’ economy that rested on five common pillars of any market economy:

1) Private ownership and property rights 4) Competition, and

2) Price system 5) Moral-hazard problem.

3) Entrepreneurship

A comparison below (Table 1) provides an important insight that could explain the differences between ancient economies and the ‘virtually zero’ economic growth rates, registered at the time. Scholars have tried to explain why the ancient economies were not growth-oriented, i.e. why there was virtually no growth in ancient times (see Maddison 2006a, 2006b). Reading Kautilya provides a crucial evidence to answer such questions. He was convinced that market is basically un-ethical and corrupt, and therefore the State, in synchrony with Dharma, must control it. Profits and incentives were under the government’s control, likewise were the price system and trade.

Table 1 Market economy comparison to Kautilya’s economy

|

Modern market economy |

Kautilya’s market economy |

|

• Private ownership (capital and resources owned by individuals) |

• Private and State ownership (capital and resources owned by a State and individuals) |

|

• Price system (used to allocate resources in the economy by the forces of supply and demand) |

• Price system (used to allocate resources in the economy by the forces of supply and demand under government’s supervision and intervention) |

|

• Entrepreneurship (invisible hand and risk-taking) |

• Entrepreneurship (invisible hand under government’s supervision and controlled risk-taking) |

|

• Competition (rivalry between buyer and sellers on the market, encouraging efficient and wise use of resources in the production process) |

• Competition (rivalry between buyers and seller under control of the State, promoting and safeguarding efficient and sustainable use of resources. |

|

• Existence of moral-hazard problem |

• Controlled moral hazard by the State |

|

Total: Efficient Market Economy |

Total: Moral Market Economy |

The state was the most important pillar of the society, and therefore in charge of supervision and controlling everything, including the market. Ancient civilizations were advanced and developed, but they were not growth-oriented, because the government and State were in charge of massive investments in public infrastructure and dwellings. Investments were important for development; cities were built, aqueducts, roads and other institutions important for the society, but there were no investments in equipment and technology. Capital accumulation in terms of fixed assets was significant, but once again, with no inherent stock of equipment and technology.

As a consequence, economic growth could not be achieved. The fact is that economic growth around 1st BC was virtually zero. The conclusion we derive from our analysis is that moral market economies, such as Kautilyan or State-oriented, as Greek, Chinese and Roman, could not earn high economic growth rates. Only market economies that are relying indisputably on invisible hand of Adam Smith, with high incentives in the form of profit, wages, interests, can accomplish high growth rates. However, such an explanation is economically insufficiently sound. In Indian tradition, Kautilya tried to build a special type of economy, which we could call a moral market economy. This is evident from the following excerpt from Sihag’s work:

‘The problem of shirking (called a moral hazard problem) and the sellers which are not providing full information to the buyer (called asymmetric information problem) are labelled as information-based market failures. Although Kautilya could not imagine that today such things would be called information-based market failures, and even though he certainly did not develop any theoretical model; he went even much further than the classical economists. Not only did he understand many of them, but he also applied them appropriately to specific situations. Similarly, he did not make any formal distinction between ‘hidden actions’ and ‘hidden information’, but he showed his awareness of such distinctions, and suggested postmodern solutions to deal with them.’ [22]

In our modern world, everything is being controlled by sophisticated technology. People are often frustrated by the lack of protection and regulations, especially in case of use of Internet, buying/selling of properties and many other everyday routine activities. For Kautilya, consumer’s protection was very important for the welfare of the population. He speaks about ways of stealing (so that consumers could pay more attention). He lists all the types of false balances used by goldsmiths, the charges and the time allowed for washing by washman and provides guidelines for compensation for the lost or destroyed goods. What is interesting for us to note is that, as he says, the guild (and every craftsman) should be responsible for the entrusted goods.

Physicians also found their place in Kautilya’s work and thoughts—they had to inform the authorities before undertaking any treatment that could involve danger to the patient’s life. Besides these remarks, the punishments have also been listed, as for all other topics that could have impact on the destabilization of the social order. In the absence of a fully developed competitive market and product warranties, consumers could use all the protection afforded by the government. Kautilya’s recommendations were almost as specific as the Clayton Antitrust Act (1914) in defining the illegal behaviour of the monopolies in the U.S.

Finally, to think about marketing as one of the inventions of modern times, mass-market consumer society and economic liberalism, seems to be spurious at least. Kautilya makes reference to the marketing system. Products of the countryside had to be sold on city markets after the payment of a duty, the sales of goods produced on Crown property were centralised, but merchants could have been authorised to sell Crown commodities in different places at a price fixed by the Chief Controller of State Trading. Imported goods had to be sold in as many places as possible. And in order to make them available to all people, the following incentives had to be provided:

‘Local merchants who bring these goods by caravans or water routes shall enjoy exemption from taxes, so they can make a profit and foreign traders shall not be sued in money disputes, but their local partners can be sued. He gives rules about profit margins as well; 5% for locally produced goods and 10% for imported goods. The price had to be fixed according to the investment, duty, interest, rent and other expenses. As we have noticed, there are detailed rules, advice and guidelines that are given throughout the text; account on customs duty, escort charges for the caravans, the cost of hiring boats and other things as well.’ [23]

Was there a market mechanism that was setting the price of the agricultural product (and not only of it), or were prices set randomly? Fortunately, The Arthashastra provides us with the evidence of a fully operational market economy that existed in the Empire. This is clearly visible from the following paragraph:

‘When there is an excess supply of a commodity, the Chief Controller of State Trading shall build up a buffer stock by paying a price higher than the market price. When the market price reaches the support level, he shall change the price, according to the situation.’ [24]

Not only that a market mechanism was present, but also a detailed and well-organized price support scheme for agricultural products existed. Evidently, the invisible hand that operated then was strictly under control and oriented to the principles of maximizing consumer satisfaction rather than towards profit maximization. Since King’s first priority was the welfare of his people, Kautilya rightfully suspected that unrestrained profits could lead to unfair trading, which is definitely not in the best interest of the citizens and thus associated with the level of welfare. Severe punishments were prescribed for merchants and traders that did not obey the rules and laws of fair-trading.

The welfare economics

Scholars working on the Kautilya’s writings often consider the economy of the Mauryan Empire as ‘socialized monarchy’ [25] or ‘state socialism’ [26], while some of them identify it as a regular welfare state. Let us refer to this last. It did not receive too much credit from the scholars, since the welfare state concept is traditionally attributed to the Western economies, especially Britain, during the industrial revolution.

Orthodox economists would say that any idea of a ‘welfare state’ during the time of The Arthashastra is an anachronism. Welfare state demands a strong and modern economic system behind it, having no place for a King in it. The Arthashastra offers evidence to historical economists and economic philosophers that welfare policy mechanism existed in the ancient Mauryan empire. To support this notion, we have to explore the link and the correlation between Kautilya’s notion of welfare state and economic foundations behind it. In other words, we have to explore growth - welfare relationship. We have already stated above that, without doubt, Kautilya has identified all the central economic pillars that could and should support his welfare state concept. In his system there were three pillars: agriculture and cattle breeding, productive manufacturing and trade [27]. He considered all three as productive activities and the only activities responsible for creation of material wealth. Inactivity, in turn, creates material distress.

Detailed analysis of each welfare regulation would surpass the purpose of this paper, just as a detailed discussion about the contribution of different disciplines to Kautilya’s work would too. Our aim here is to highlight the social ethics that was present in all aspects of life then, and thus in economics as well. The protection of elders, the welfare of all social groups according to their status, the welfare of animals, the protection of consumers and women, child, widows etc. combined into a full set of regulations and suggestions given by Kautilya to show how a welfare state should look. Although strict rules and controlled trade and social life could diminish his contribution to ideas regarding social ethics, everything that was displayed in his texts shows not only the character of a great individual, but more importantly, a compendium of knowledge and values that were neglected for centuries by most scientists and public.

We have observed that his government orientation to provide social security and welfare for the citizens is inherent in the number and quality of measures the State undertakes to achieve the welfare goal. This rules out the rhetorical assumption of the King’s role in promoting well being of the people or the idea of a welfare state bounded to a certain point in time in the evolution of human and society. Number and details on the measures to be taken by the King and government officials to promote welfare described in The Arthashastra support our contention. Here, we can cite from the famous opus some important aspects and activities that promote social security and well-being:

Protection of the weak: Therefore, he should look into the affairs of temple deities, hermitages, heretics, Brahmins learned in the Vedas, cattle and holy places, of minors, the aged, the sick, the distressed and the helpless and of women, in this order, or, in accordance with the importance of the matter or its urgency.

Child and elderly, social protection: And the King should maintain children, aged persons and persons in distress when these are helpless, as also the woman who has borne no child and the sons of one who has (when these are helpless).

State supports and benefits: Brahmins, wandering monks, children, old persons, sick persons, carriers of royal edicts and pregnant women should cross with a sealed pass from the Controller of shipping (free of charge).

Equality before the law: The judges themselves shall look into the affairs of gods, Brahmins, ascetics, women, minors, old persons, sick persons, who are helpless, when these do not approach (the court), and they shall not dismiss (their suits) under the pretext of place, time or (adverse) possessions.

Protection and privileges in the labour market: Superintendent of Yarns should get yarn spun out of wool, bark-fibres, cotton, silk-cotton, hemp and flax, through widows, crippled women, maidens, women who have left their homes and women paying off their fine by personal labour, through mothers of courtesans, through old female slaves of trekking and through female slaves of temples whose service of the gods has cease.

Elderly to child protection: The elders of the village should augment the property of a minor till he comes of age, also the property of a temple. [28]

Finally, If a person with means does not maintain his children and wife, his father and mother, his brothers who have not come of age, and his unmarried and widows sisters, a fine of twelve panas (shall be imposed) except when these have become outcasts, with the exception of the mother. [29]

Social security and well-being was both a private and a State matter. The head of the household was in obligation to look after the members of the household and ensure their well being. The State, on the other hand, had a responsibility to provide job support and assistance to the head of the household so that he could take care of his family. The State’s welfare policy was mainly oriented to the needs of the helpless and people in need for help, so as to enable them to retain a social status equal to that of average people in the Empire. In accordance, State funds were primarily allocated to these social groups and providing all that is needed for an efficient and productive economic activity. Education and Health services were not a State affair but were matter of private interest. This fact is clear from the government organizational structure itself with no department and Chief State officers in charge for education and administering health. Income inequality was large. Except for the King, who controlled all the property of the State, the highest to lowest income ratio within the Empire was 800 [30]. Mauryan state provided a level of social security and welfare perhaps highest possible at that time. Evidence on the existence of health insurance agencies and other forms of health risks hedging is not available. Fact remains that the state engaged in the wars and defence could not look at every aspect of the social life. Social security, therefore, had to be of private interest and not only the State problem. Since, no data on poverty is available for that period we are not in a position to compare the efficiency or social consciousness between Kautilyan and ‘modern’ welfare states. Strong testimony on State’s commitment to the welfare policy rested upon the rules for protecting people against corrupt state officials. Corruption was perceived as the main threat to social security at the time.

‘And in the case of false statement by these, the fine shall be the same as for the officer (concerned). And he should issue a proclamation in the sphere of his activity. Those wronged by such and such an officer should communicate (it to me). To such as communicate he should cause payment to be made in accordance with the injury suffered.’ [31]

The resolute fight against corrupted officers by government officials shows beyond doubt that there was a high level of social consciousness on the part of the State to protect the public interests. The objective of economics as a science is to study the process of wealth creation and find ways to improve the living standards of the people. Just as Adam Smith, in increasing division of labour, saw the opportunity for economic growth, Kautilya marks productivity as the key growth factor.

The concept of welfare state is particularly important in the context of the qualitative differences between ancient and modern societies. The Arthashastra paragraph that follows clearly asserts what economic activity is, why it is important to the king and how it should be managed. In other words it reflects the economic theory of the time. Hence the king is the principal actor:

‘The root of wealth is (economic) activity and lack of it (brings) material distress. In the absence of (fruitful economic) activity, both current prosperity and future growth will be destroyed. A king can achieve the desired objectives and abundance of riches by undertaking (productive) economic activity.’ [32]

We must say that the hypothesis of primitivity of Kautilyan economic model and his economy is unsustainable. There is more than enough evidence against such a hypothesis in our analysis and in work itself. Kautilya’s magnum opus contains all the elements of the modern economic thought. The Kautilyan economy must function in synchrony with Dharma, else it is doomed to failure, exactly in the sense Adam Smith means: ‘(…) it is the invisible hand that pushes the world forward, but we do not know where and how it will end.’[33] Kautilya saw the solution to the problem in the form of moral market economies.

From Arthashastra to modern economics

Kautilya’s economic thought is definitely a milestone in contribution to the advancement of economic science in the fields of labour economics, growth theory, international economics, marketing, public policy management, fiscal and monetary policy, welfare economics etc. We can observe from his writings that his doctrines were based on facts and hypotheses of the time and these served as cornerstone to the pre-classical economic schools. We can safely regard him as the first pre-classical economist. His doctrines are the result of his analytical and synthetic work springing from the economic realities of the mighty Mauryan Empire.

This fact is very well evident if we search for clues in the ancient economic thoughts. His doctrines convince us that just as the western classical economics so the 20th century Keynesian belief tacitly incorporated some of his views on moral and scientific issues. Threads of link from Kautilya to Smith can be traced in the fact that while Adam Smith built a comprehensive, systematic theory of 17th century economics, Kautilya offered a much more elaborate and systematic theory of 4th century B.C. India.

Kautilya, like Adam Smith, did not focus on a single element of the economic system but looked at it as a whole connecting each and every element with the sole purpose that the system generates and accumulates wealth based on free trade (in Smith’s model) and strong agricultural production (Kautilyan case). A free market operates under natural laws (in Smith’s case) and under conspicuous eyes of the State (in Kautilyan model). Country’s wealth accumulation is a function of marketable land and labour production (in Smith) and direct result of any material activity and inactivity causing wealth depletion (in Kautilya). While, according to Smith, division of labour increases production and innovation depending upon the size of market, in Kautilya, it is directly related to labour productivity. Economic growth process is based on productive labour (Smith) and productive enterprises (Kautilya). Market price is a result of interaction of natural market forces at which any commodity is sold (Smith) and market mechanism under State stabilization policy (Kautilya). Wages are negotiated on bargaining and contract (Smith) or as labour productivity wages (Kautilya). Since, in the Kautilyan system, the sole purpose of trading was to promote people general welfare, the profit margins are fixed at 5 and 10 per cent (for selling local and imported goods respectively). Profits, as Smith believed, have an inherited tendency to fall (i.e. wage-profits inverse relation) and are directly related to labour productivity in Kautilya. Table 2 provides a comparative picture of views expressed by Kautilya and Adam Smith in their respective works.

Interesting enough, almost two thousand years before David Ricardo, Kautilya advances a labour theory of value with wages being determined by the market value, production-cost relations, and quantity of labour employed. Kautilya, just like Ricardo, built a differential theory of rents and distribution connecting values with scarcity and quantity of labour and its quality (human capital). While the Recardian wages, or the natural price of labour as he calls it, depends on the labourers costs of subsistence (food and necessities), Kautilya proposes that labourers should be paid a proportional wage as to the time and skill (measured by quality of product) so as to protect their welfare and his family’s minimum subsistence level. Evidently, Kautilya is arguing for the labourer’s natural wage, a wage that is not derived from commodity’s final market price (forces of demand and supply) or profits. According to him, the lowering the means of subsistence through the so called natural wage drop, will in turn result in scarcity of labour supply, falling consumption demand and thus, falling profits and economic growth.

Kautilya, like Ricardo develops a differentiated theory of rents depending not only on the quality of land but also on the quality of labour (skilled and unskilled labourers) with heavy fines and even confiscation of the land from proprietors those not using it efficiently and for productive purposes.

Table 2 A comparative view of Arthashastra and The Wealth of Nations

|

The Arthashastra |

The Wealth of Nations |

|

• Factor costs of production |

• Inputs |

|

• Profit and profit margins |

• Greed and speculation regulation |

|

• Resources |

|

|

• The division of labour and specialization |

• Division of labour and growth |

|

• Supply and demand rules on the market |

• Free markets |

|

• Technology |

• Industrialization |

|

• Equilibrium on the commodity market which in turn determines the level of employment, real and efficiency wage, and the price level in the State |

• Free markets role in recessions and depressions |

|

• Efficiency and productivity wage |

• Minimum and adequate wage |

|

• Monetary equilibrium and inflation problem |

• Money and spending |

|

• Money and deposits |

• Stable currency |

|

• Price support for agricultural products |

• Public goods and markets |

|

• Sources of income and expenditure for the State |

• Size and scope of government |

|

• Budget and budget policy |

• Government efficiency |

|

• Trade and trade policy |

• International markets and prices |

|

• Market and state, private ownership and private ownership’s protection |

• Property rights and wealth generation, property rights protection |

|

• Monopolies (state or natural) vs. perfect competition |

• Public goods and efficiency, market failures |

|

• Fiscal policy including taxes, transfers, debt-management, treasury |

• ‘Strong’ governments disseminate private sector inadequacies |

|

• Productivity and economic growth |

• Division of labour, productivity, growth |

|

• Welfare economics (welfare state) |

• Free markets and unequal income distribution |

Further, Kautilya has developed a modern and complex theory of international trade and comparative advantage in no sense inferior to Ricardo’s. We must appreciate his wisdom, as he places an equal importance on the imported and exported commodities. He asserts that exported commodities through money exchanges increases wealth accumulation (in other words, gains from trade); therefore, an equal attention should be paid to empire’s export policy and export orientation towards highly profitable areas where to sell the Crown commodities such that unprofitable areas should be avoided (costs of trade). Imported goods, he did not consider inferior to exported goods since imports of the foreign goods are needed inside the country, these increases country’s wealth just in the same way as exported commodities. Not only that, he advocated that imported goods should be distributed across the country in accordance with the rule of allocative efficiency.

Similarities can be also be found between some views of Kautilya and some of Malthus, particularly with respect to economic inequality, self-interest and public welfare, nature of economic progress and its future, religion and poverty. Karl Marx, following Smith’s doctrine, believed that economic growth is a result of increasing productive capacities and profits resulting from the gap between natural wage and produced commodity values. Likewise, Kautilya sees economic growth as a direct consequence of productive labour and productive enterprise with the State obligation to monitor profits and that labourers are paid on the basis of the principle of just labour equal to just wages. Profits were aloud but not at the expenses of just wages. Evidently, in Marxian sense, it reflects a care for labour’s interest. Kautilya and Alfred Marshall both consider demand for the factors of production and wages to be determined by the marginal-productivity relationship such that prices fluctuate around marginal costs. They share a common line of thought about development and growth also. Large expenditure followed by a small increase in wealth is not to be considered economic progress but merely a physical (organic) growth of production. Evidently, Kautilya, like Alfred Marshall makes a clear distinction between progress and growth. While economic system in Marshall’s opinion is just one part of the unity—economic, political, social, cultural and institutional settings and economics as a science that connects the study of wealth cycle and the mankind; Kautilya’s The Arthashastra literally does the same: ‘the science of wealth’ studying all aspects of economic life (poverty, welfare, growth, exchange, trade, wage) under natural law of Dharma. Kautilya long before Marshall has advanced an ‘organic growth theory of society’ based on conjoint economic development of society and the human nature. Alfred Marshall, too, focused on his economic theory by trying to explain how and why economic system progresses and tried to link it with the development of society. However, the fundamental question both for Kautilya and Marshall remained – does the economic system progresses as society develops or it is the economic progress that drives the society’s development?

Close resemblance between Arthashastra and The General Theory of Keynes is visible in the demonstrated need of positive role that the State should play in the economic system. In both works, markets have been assigned an important role within the society; but both stress that economic progress can not be achieved without an ‘active’ role of the State. Kautilya and Keynes, both believed that markets can not manage productive activities by themselves, and that within a well developed institutional framework, help from the State in its role of ‘General Manager’ responsible for macroeconomic managing, is highly desirable. To both, the aggregate demand is too important for the economic growth to be left wandering around by itself. Private sector has neither full knowledge (on how the rest of the system works) nor is interested beyond its profit, the State must, therefore, protect the economic system from the occurrence of business cycles and the shocks inherited from with in or from outside the system.

Furthermore, we strongly feel that modern economics must offer an objective evaluation of Kautilya’s contribution to the development of the economic science. His should be seen as a ‘cumulative theory’ and should receive due credits. His doctrine contains elements that are carried over not only in the classical school (placing him as first pre-classical theorist) but also in Marxian, Neoclassical and Keynesian schools of economics. He was the first political economist to construct a comprehensive growth model with a theoretical background incorporating Marshalls’ ‘organic economic growth’ concept (completely different from mainstream growth theories that bounce out completely the human nature and man from all equations). However, Kautilya much before Marshall shaped economic growth and progress as the ‘final frontier’ that mankind must cross and not just answer ‘why the nations grow’.

Conclusion

The arguments we advance in this paper leave little doubt that Arthashastra conceals an important contemporary relevance for the modern economics theory. A systematic study of political economics, Arthashastra is a major contribution to economic theory and, as such, deserves rehabilitation of its long forgotten proper place in the history of modern economic thought. Kautilya could surely be called as the first political economists and precursor to classical economic thought.

In the Phillipsian sense (1962) of economics as a science that tries to explain ‘how the system works’, we can consider The Arthashastra to be the missing link in between pre-classical and modern economics that shows the evolutionary path by providing a valuable insight into the policies and practices of the time. Kautilya’s contribution to economics is commendable, as by studying his The Arthashastra we can not only learn about the methodological problems of the time, scope of their inquiry, and reality of their assumptions, but also gather knowledge of the methodological, epistemological and practical problems of modern economics. In the end, we can say with great confidence that Arthashastra is evidently an important systematic study of the political economy of the time. Economic concepts and variables that we can identify in the Kautilyan model leave us with no doubt in our mind that these are the same standard exogenous and endogenous variables that construct any modern economic model.

Endnotes

[1] Both Indian and classical historical sources agree that Chandragupta, the chief architect of greatest of India’s ancient empires, overthrew the last occupant of the capital city of Pataliputra around 320 BC. According to all Indian tradition, he was much aided in his conquests by a very able Brahman adviser and minister called by various names: Kautilya, Chanakya and Vishnugupta, being the real ruler of the empire. He is the reputed author of the Arthashastra, or Treatise on Polity. Some scholars maintain the authenticity of the authorship ascribed to Kautilya, but there are some doubts about the date of its composing (Mabbett 1964).

[2] Arguments for their theory of knowledge can be found in Schumpeter (1996) as a rich harvest has resulted in falling prices in themselves do not contain scientific knowledge and discovery. We could imply that lack of scientific causation between rich harvest and falling prices is just common knowledge, as often is a case in economics. We believe that such formal causation is rather too simplistic to be considered scientific. At the best it is prescientific.

Article Courtesy: The Journal of Philosophical Economics VI:2 (2013) Škare, Marinko (2013) ‘The missing link: From Kautilya’s The Arthashastra to modern economics’, The Journal of Philosophical Economics, VI:2