Abstract:

The main objectives of this paper are of two kinds: first one may be described as historical in the sense of correcting more than two thousand years of misinterpretations of the ideas of Confucius and Kautilya on establishing a moral order and the nature of its relationship to the legalistic approach; the second one is to highlight the relevance of moral order not only to create peace and harmony but also enhance the creation and sharing of knowledge and lowering of transaction costs.

Since both creation and sharing of knowledge depend on genuine trust, which flourishes only in an ethical environment, and not in a “culture of suspicion”. It is indicated that their insights or pearls of wisdom are actually more relevant to today’s knowledge-based economies than they were to economies during their own times. They would have emphasized the warming of hearts to each other to solve the problem of global warming.

1. Introduction: Confucius (551-479 BCE) was a humble, ethical, foresighted, wise and religious person. He might have briefly served as a minister of justice and also as a Prime Minister but essentially he was a teacher. He believed in ethical education of the young.

Kautilya was simple, foresighted, ethical, secular and wise. According to Indologists, he wrote his Arthashastra, a manual on engineering shared prosperity, during the 4th century BCE. However, new research has challenged the view and claims that he lived many centuries earlier than the fourth century BCE.

Both Confucius and Kautilya were original thinkers and advocated establishment of a moral order. They did not reject the legalist approach rather considered it as complementary, but definitely not a substitute, to the ethics-based approach. They firmly believed that legalist approach alone could not bring peace and prosperity for all the people.

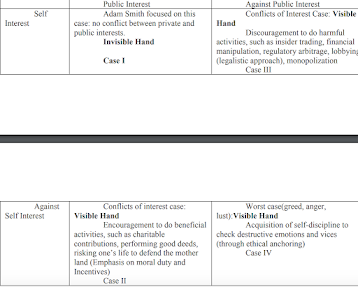

Confucius, Kautilya and Kautilya’s predecessors wanted to create a peaceful and harmonious society. They assigned a foundational role to moral order. Although Confucius primarily focused on the ethical approach but he was not naïve to ignore the relevance of laws. Kautilya, however, along with the ethical approach, also developed cardinal principles of justice, and suggested contract laws, property rules and tort laws (see Sihag, 2014, Chapters 6, 15, 16 and 17, [1]). Both Confucius and Kautilya believed that law and order, to a large extent, depended on good ethical conduct. They understood the limitations of a legalist-approach that it did not emphasize or promote self-discipline, which could be acquired only through ethical anchoring, implying that it could never help in controlling excessive greed, the major source of corruption. They essentially linked market failure to government failure and government failure to moral failure. They not only had similar views on the need to establish a moral order but also had similar views on other topics. These are presented in Section 2.

Establishment of a moral order is essential to the creation and sharing of knowledge and also to the reduction of transaction costs. An opportunistic environment is not very conducive to knowledge creation and its sharing, which are the main characteristics of a knowledge-based economy. Economists and organizational scholars believe that it is not possible ex ante to differentiate a trustworthy person from an untrustworthy one, so it is prudent to adopt a “calculative” approach to trust, that is, treat trust as a risk. Complex contracts requiring expensive legal advice are written to safeguard against the potential harm that might be caused by the partners’ opportunism.

Section 3 presents the need for establishing a moral order for a creative economy. Adam Smith (1723-1790) lived at least two thousand years later than Confucius and Kautilya. He wrote two books: Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations. He, just like Han Feitzu, rejected the possibility of establishing a moral order and advocated a legalist approach. He could not introduce the benevolent man of The Theory of Moral Sentiments to the commercial man of The Wealth of Nations, although some prominent economists have been trying hard to perform a civil marriage between these two unwilling adults. Recently, Carsten Herrmann-Pillath (2011) [2] compares Confucian thinking to that of Adam Smith and finds “a number of conceptual family resemblances between the two”.

Section 4 shows that their conceptual thinking is as much apart as the North Pole from the South Pole. Transaction cost economics (TCE) approach to trust is actually a statistical approach to the building or destroying of confidence. Repeated games or familiarity breeds confidence but not necessarily trust. The common definition of trust as a person’s vulnerability to the competence and benevolence of another person or party is valid only in the current amoral or legalistic environment but not in an ethical environment. Genuine trust is an ethics-intensive concept since non-violence, truthfulness, honesty and benevolence are the foundation for trust. That is, trust flourishes only in an ethical environment. How to make sure that children grow-up to be ethical adults?

Ideas of Confucius and Kautilya on ethical anchoring of children are presented in Section 5.

Final section contains concluding observations.

2. Confucius and Kautilya on Moral Order to Prevent Government Failure :Western countries’ legalistic approach has not prevented insider trading, back-dating options, regulatory arbitrage, such as shadow banking, lobbyists influencing tax laws, environment laws, trade policies and many other policies. In other words, both the formulation and implementation of laws get compromised and thus adversely affecting the common good. That is, legalistic approach alone could not prevent government failure. There are instances where the government officers themselves participated in committing economic crimes. Additionally, legalistic approach is almost totally ineffective in preventing crimes resulting from anger or lust.

Kautilya [3] observed a long time ago that ‘greed clouds the mind’ and similarly lust and anger, the other destructive passions, overpower the reasoning faculty. Confucius’s List of Virtues: “Speak the truth, do not yield to anger; give, if thou art asked for little; by these three steps thou wilt go near the gods. To practice five things under all circumstances constitutes perfect virtue; these five are gravity, generosity of soul, sincerity, earnestness, and kindness. Virtue is more to man than either water or fire. I have seen men die from treading on water and fire, but I have never seen a man die from treading the course of virtue.”

Kautilya’s List of Virtues:

Kautilya [4] (p. 107) listed ethical values as: “Ahimsa [abstaining from injury to all living creatures]; satyam [truthfulness]; cleanliness; freedom from malice; compassion and tolerance.”2 Foundational Role of Ethics: Both Confucius and Kautilya are unique in assigning a foundational role to ethics but were not naïve to ignore the importance of legalistic approach.3 They wanted the legalistic approach to complement the ethics-based approach not substitute it. For example, Kautilya argued that ethical environment was essential to the maintenance of law and order. He [4] (p. 142) wrote, “Government by Rule of Law, which alone can guarantee security of life and welfare of the people, is, in turn, dependent on the self-discipline of the king (1.5).” He (p. 106) wrote, “[The observance of] one’s own dharma leads to heaven and eternal bliss. When dharma is transgressed, the resulting chaos leads to the extermination of this world.” He further expanded the role of ethics. He argued that ethics was the most effective catalyst in attaining salvation from poverty. He (pp. 107-108) asserted, “For the world, when maintained in accordance with the Vedas, will ever prosper and not perish. Therefore, the king shall never allow the people to swerve from their dharma.”

Similarly, Confucius believed, "The perfecting of one’s self is the fundamental base of all progress and all moral development. He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it. If the people be led by laws, and uniformity sought to be given them by punishments, they will try to avoid the punishment, but have no sense of shame. If they be led by virtue, and uniformity sought to be given them by the rules of propriety, they will have the sense of shame, and moreover will become good.” On the other hand, both Han Feitzu and Adam Smith rejected the ethics-based approach and advanced only the legalistic approach.

Confucius on Controlling Vices: "When anger rises, think of the consequences. There are three things which the superior man guards against. In youth, when the physical powers are not yet settled, he guards against lust. When he is strong and the physical powers are full of vigor, he guards against quarrelsomeness. When he is old, and the animal powers are decayed, he guards against covetousness.”

Kautilya on Controlling Vices: Kautilya [4] (p. 137) explained, “Vices are due to ignorance and indiscipline; an unlearned man does not perceive the injurious consequences of his vices (8.3).” He (p. 144) stated, “The sole aim of all branches of knowledge is to inculcate restraint over the senses (1.6.3). Self-control, which is the basis of knowledge and discipline, is acquired by giving up lust, anger, greed, conceit, arrogance and foolhardiness. Living in accordance with the shastras means avoiding over-indulgence in all pleasures of [the senses, i.e.,] hearing, touch, sight, taste and smell (1.6.1, 2).” Confucius on Good Governance: “When a country is well governed, poverty and a mean condition are something to be ashamed of. When a country is ill governed, riches and honors are something to be ashamed of. There is good government when those who are near are made happy, and when those who are afar are attracted. To rule a country of a thousand chariots, there must be reverent attention to business, and sincerity; economy in expenditure, and love for men; and the employment of the people at the proper seasons. An oppressive government is more to be feared than a tiger.”

Kautilya on Good Governance: Kautilya emphasized the provision of infrastructure, fair, clean and caring administration (see Sihag (2014: Chapter 8) for details [1]). Kautilya (4th century BCE/2000, p. 88) [3] observed, “The ruler’s duties are stated to be five: punishment of the wicked, rewarding the righteous, development of state revenues by just means, impartiality in granting favours and protection of the state.” He emphasized clean administration. He (4th century BCE/1992, pp. 493-494) asserted, “Thus, the king shall first reform the administration, by punishing appropriately those officers who deal in wealth; they, duly corrected, shall use the right punishments to ensure the good conduct of the people of the towns and the countryside (4.9).”

Confucius on Role Model: “By the ruler’s cultivation of his own character there is set up the example of the 2 Dhar (2003: pp. 156-157) [14] observes, “Our tradition recognizes certain eternal values including love, compassion and non-injury. It underscores the importance of means being right to achieve right ends.” On the other hand, Staveren (2001: p. 153) [15] asserts, “Central to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics is that virtue can only be found by trial and error as a mean between efficiency and excess: virtue depends on deliberation, as I argued in chapter one. It is important to repeat Aristotle’s view that virtues are not pre-given, they are not universals, nor subjectively prescribed in individual objective functions.” 3 Richard Kraut (2010) [16] observes, “What Aristotle has in mind when he makes this complaint is that ethical activities are remedial: they are needed when something has gone wrong, or threatens to do so. Courage, for example, is exercised in war, and war remedies an evil; it is not something we should wish for.” course which all should pursue. When superiors are fond of showing their humanity, inferiors try to outstrip one another in their practice of it. When rulers love to observe the rules of propriety, the people respond readily to the calls on them for service. If a minister make his own conduct correct, what difficulty will he have in assisting in government? If he cannot rectify himself, what has he to do with rectifying others?”

Kautilya on Role Model: He (p. 147) wrote, “If the king is energetic, his subjects will be equally energetic. If he is slack and lazy in performing his duties the subjects will also be lax and, thereby, eat into his wealth. Besides, a lazy king will easily fall into the hands of his enemies. Hence, the king should himself always be energetic (1.19).” He (p. 121) stated, “A king endowed with the ideal personal qualities enriches the other elements when they are less than perfect (6.1).” He (p. 123) added, “Whatever character the king has, the other elements also come to have the same (8.1).”

Confucius on Bounded Rationality: “Ability will never catch up with the demand for it. To know what you know and what you do not know, that is true knowledge. Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance. The superior man is distressed by his want of ability. He is not distressed by men’s not knowing him.”

Kautilya on Bounded Rationality: “A king can reign only with the help of others; one wheel alone does not move a chariot. Therefore, a king should appoint advisers (as councilors and ministers) and listen to their advice.” Kautilya (p. 177).

Confucius on the Role of Foresightedness: “If a man takes no thought about what is distant, he will find sorrow near at hand. He who does not anticipate attempts to deceive him, nor think beforehand of his not being believed, and yet apprehends these things readily (when they occur);—is he not a man of superior worth?”

Kautilya on the Role of Foresightedness: “In the interests of the prosperity of the country, a king should be diligent in foreseeing the possibility of calamities, try to avert them before they arise, overcome those which happen, remove all obstructions to economic activity and prevent loss of revenue to the state (8.4).” Kautilya (4th Century BCE, p. 116) [4]. 3. Relevance of a Moral Order to a Creative Economy Trust Key to Creation and Sharing of Knowledge: Lukasz Hardt (2009) [5] discusses the transaction cost economics (TCE) in a knowledge-based economy, which he labels as a second cognitive turn. He (p. 44) remarks, “Therefore, when problems are non-decomposable, searching best takes place within the firm, and when they are decomposable the market will be a more efficient machine for organizing searching. In this approach the firm is able to produce valuable knowledge (or, in other words, to solve problems).” Note, the above statement explains the efficiency gains in ‘organizing searching’ and producing knowledge by a firm. However, the level of positive gains from creation and sharing of knowledge depend on the level of trust since it is the mutual trust which binds the knowledge workers together.

Characteristics of a Knowledge-based Economy: First, a knowledge-based economy may be characterized as one in which intangibles are more valuable than the tangibles. Innovation is the source of survival and sustainable economic growth, that is, innovate or perish. Knowledge-intensity in almost every product/service is relatively higher and rising. Knowledge has characteristics of a public good and usually there exists more tacit knowledge than explicit knowledge. Second, a creative economy is very different from an industrial economy. Knowledge workers need flexibility and the old assembly line approach, which was labeled as Fordism, does not work. Third, the market for ideas is, at best, imperfect. The buyer does not know what s/he is buying and the seller does not know what s/he is selling. Since the potential of an idea is never known with certainty.

Critical Role of Trust in a Knowledge-based Economy: Trust may be an intangible asset/good but has the most tangible role in creating and sustaining the social, economic, cultural and political structures. It is the brick and mortar to the building of inter-personal relationships.

Emphasis on the Power of Pooling Knowledge and Information: Kautilya’s predecessors understood the importance of sharing information and knowledge to arrive at the most efficient decision However, Trust is the most valuable asset in a knowledge-based economy. Both creation and sharing of ideas depend on trust. The distinguishing characteristic of a knowledge-based economy is a frequent sharing of tacit knowledge and exchange of information among the cognitive labor. As soon as a person codifies his/her tacit knowledge everyone has access to it. Knowing this fact a person will share tacit knowledge only if s/he is sure of not getting fired. It is indicated in section IV below that creating ethical-based trust is the key to realizing all the potential gains from creating and sharing of knowledge. B. S. Sihag 24 Williamson (1985: p. 47) [6] characterizes the potential behavior of the other firm as: “calculated efforts to mislead, disguise, obfuscate, or otherwise confuse” and “seeking self-interest, but they do so with guile”. In the prevailing opportunistic and legalistic environment it would be naïve or even foolish to trust anyone since that would be too risky. Interestingly, Machiavelli had very similar views. He (1513: p. 52) [7] wrote, “For of men one can, in general, say this: They are ungrateful, fickle, deceptive and deceiving, avoiders of danger, eager to gain.” He continues, “Men are less nervous of offending someone who makes himself lovable, than someone who makes himself frightening. For love attaches men by ties of obligation, which, since men are wicked, they break whenever their interests are at stake.” He (p. 73) adds, “This is how it has to be, for you will find men are always wicked, unless you give them no alternative but to be good.”

Trust and Transaction Costs: Compared to a moral society an amoral or immoral society would incur increasingly burdensome transaction costs. Since a prudent person or firm could not afford not to undertake protective measures. Consequently, each firm ends up devoting a considerable amount of resources to protect itself against opportunism. Everyone tries to outsmart the other party to the contract by negotiating and writing a good contract, which leaves no room for conscience or compassion. The increasing share of transaction sector, the rising number of tort cases, increasing cost of defensive medical practice, rising cost of enforcement indicate that, may be in the long run, such rising transaction costs would make the purely contract-based economies lose their competitive edge. In sum, trust a) reduces transaction costs by reducing opportunism, enhances a feeling of wellness by reducing anxiety and b) also might increase GDP by reducing the demand for lawyers and turning them into engineers. It may also be noted that the relational contracts are experience-based and are not based on any ethical foundation implying they may not create any trust and thus the possibility of opportune behavior is not precluded. Secondly, relational contract may lead to poor quality as one party may too readily accommodate the requests of the other party. For example, Ford Motors and Firestone Tires Company had almost 100 years of business relationship and consequently Firestone Tires Company was not strict on requiring Ford Motors to maintain the desired air pressure in the tires and thus compromising safety, that is, their relationship had become too cozy. Both companies were sued and the costs of litigation and compensation to the consumers were huge. Additionally, reliance on contracts alone might cause an erosion of ethical values (called crowding out). 4.

Adam Smith on Infeasibility of Moral Order: Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments has over 400 pages but does not explain the concept of virtue and did not assign any foundational role to virtue ethics.4 Adam Smith ([1790] 1982: VII. 1.2, p. 265) [8] states, “In treating of the principles of morals there are two questions to be considered. First, wherein does virtue consist of? Or what is the tone of temper, and tenour of conduct, which constitutes the excellent and praise-worthy character, the character which is the natural object of esteem, honour, and approbation?5 And secondly, by what power or faculty in the mind is it, that this character, whatever it be, is recommended to us? Or in other words, how and by what means does it come to pass, that the mind prefers one tenour of conduct to another, denominates the one right and the other wrong; considers the one as the object of approbation, honour, and reward, and the other of blame, censure, and punishment.” Raphael (2007: pp. 71-72) [9] comments, “Smith gives us a full and clear account of the content of virtue, that is, the cardinal virtues and the relation between them, but fails to provide an enlightening explanation of the concept itself, as he does with the topic of moral judgement. Such an explanation would show how the concept of moral virtue arises and how it distinguishes moral excellence from other forms of human excellence.” Apparently, according to Raphael, Adam Smith’s The theory of Moral Sentiments has essentially no theory implying that the controversy over “Adam Smith’s problem” is a futile one. Also, lack of a theory, perhaps has been one big reason that only economists have shown such an interest in it.

Adam Smith assigned no Foundational Role to Virtue Ethics: Adam Smith ([1790] 1982: II. ii. 3, pp. 3-4) believes, “Beneficence, therefore, is less essential to the existence of society than justice. Society may subsist, though not in the most comfortable state, without beneficence; but the prevalence of injustice must utterly de4 Adam Smith could not borrow from the Greek philosophers since they also did not define virtue. Jim Holt (2006) [17] points out, “Aristotle defined virtue as a quality of character that makes for a life well lived. Then he characterized the good life as a life lived in accordance with virtue. Circular?” 5 Confucius: “In ancient times, men learned with a view to their own improvement. Now-a-days, men learn with a view to the approbation of others.” On the other hand Adam Smith puts too much emphasis on approbation. B. S. Sihag 25 stroy it.” He adds, “It is the ornament which embellishes, not the foundation which supports the building, and which it was, therefore, sufficient to recommend, but by no means necessary to impose.”

Adam Smith ([1790] 1982: II. ii., 3.4) argued, “Justice, on the contrary, is the main pillar that upholds the whole edifice, if it is removed, the great, the immense fabric of human society must in a moment crumble into atoms.” According to Adam Smith, ‘prevalence of injustice’ would destroy the edifice. However, he does not realize that lack of ethics was the sole source of injustice, discrimination, infringement, slavery and suppression. Adam Smith gives justice a foundational status but does not explain how to construct it and what upholds this pillar. A few remarks are in order. First, the pillar must be standing on the solid rock of dharma, (ethics) otherwise it would be unstable. That is, justice in an unethical society is unattainable. Second, if justice has to serve as the main pillar, then it must be strong enough to support the edifice.

However, it will not be strong unless it is constructed with the bricks and mortar of dharmic (ethical) values. Finally, it appears as if the pillar and the edifice are two separate entities and not components of one system. Every society decides both the pillar and the edifice together, but Adam Smith’s approach does not allow any possible interaction or interdependence between them. James Halteman and Edd Noell (2012) [10] explore Adam Smith’s ideas on ethics. They (p 76) remark, “The social passions are generosity, compassion, and esteem. They are inherently good and bring forth virtuous behavior, but they are also scarce and not prevalent enough in everyday life to serve as the foundation of a successful social order.” Clearly, Smith did not have a positive view of people and did not suggest any ethical education to make them ethical. His approach essentially was legalistic and very similar to that of Han Feitzu (280-233 BCE) another thinker from ancient China. Chang (1987) [11] explores the contributions of Confucius (551-479 BCE), a moral philosopher and Han Feitzu (280-233 BCE), a legalist.

Chang remarks, “The Confucian state is established on a set of ethical norms and rites—rules, ceremonies, and manners codified by legendry sages—and governed by men through moral influence, rather than law, coercion, or by divine spirits.” Chang adds, “Another outstanding legalist was Han-fei-tsu (280-233 BC), a theoretician and a disciple of Hsun-tzu. Following his teacher, Han-fei-tzu believed that basically people were motivated largely by self-interest. For the sake of social order and economic progress, Han-fei-tzu proposed strict and uniform application of rewards and punishments and rejected Confucian egalitarianism. In his view, chances for success under Confucianism were far less than under Legalism. In his assessment, the former would function well only if individuals are guided by morality and rulers are sage kings, but in reality, individuals are guided overwhelmingly by self-interest and rulers are mostly average kings.

On the contrary, Legalism, along with its laws and regulations designed for the good of the whole society headed by an average ruler, offers a greater chance of success.” Similarly, Choi (1989) [12] points out, “Han Feitzu repeatedly argued against Confucians (moralists) and showed that proposals based on moral grounds, though eloquent, inevitably resulted in absurdity if not outright undesirability”.

5. Confucius and Kautilya on Ethical Anchoring of the Young: Both Confucius and Kautilya were optimistic and believed that an ethical environment could be created. There was rampant corruption during their times and they were aware of the existing conditions. Their ultimate objective was to establish a moral order, may be in a generation or two, which ensured a richer and fuller life to everyone in the society. They argued that was possible only through ethical grounding of the young. As mentioned earlier, they were not against the legalistic approach for handling the existing situations. Confucius on Ethical Anchoring: “The mechanic that would perfect his work must first sharpen his tools. A youth, when at home, should be filial and, abroad, respectful to his elders. He should be earnest and truthful. He should overflow in love to all and cultivate the friendship of the good. When he has time and opportunity, after the performance of these things, he should employ them in polite studies.” Kautilya on Ethical Anchoring: Kautilya (pp. 155-156) suggested, “‘There can be no greater crime or sin’, says Kautilya, ‘than making wicked impressions on an innocent mind. Just as a clean object is stained with whatever is smeared on it, so a prince, with a fresh mind, understands as the truth whatever is taught to him. Therefore, a prince should be taught what is dharma and artha, not what is unrighteous and materially harmful (1.17).”

Strengthening and Sustaining Ethical Values: Company of disciplined individuals, particularly of elders was considered important in strengthening ethical values and conduct. Kautilya (p. 143) suggested, “With a view to B. S. Sihag 26 improving his self-discipline, he should always associate with learned elders, for in them alone has discipline its firm roots (1.5).” Similarly, Confucius suggested, “He who aims to be a man of complete virtue in his food does not seek to gratify his appetite, nor in his dwelling place does he seek the appliances of ease; he is earnest in what he is doing, and careful in his speech; he frequents the company of men of principle that he may be rectified- such a person may be said indeed to love to learn.”

6. Concluding Observations: Ethical environment encourages both trust and transparency, which help in changing the “culture of suspicion” and thus in reducing the need to take defensive measures. In recent years the words transparency and accountability have taken hold of our imagination. Transparency is understood as the full and accurate disclosure of relevant information in a simple format and timely fashion. Almost exclusively, the emphasis has been on rulebased transparency, such as legislations regarding shareholders right to know how much a CEO gets paid and consumers right to know the calories or fat content in the meals restaurants serve. Similarly, many regulatory agencies have been created to protect against the trust deficit rather than to eliminate the trust-deficit. There has been very little if any emphasis or effort on the ethics-based transparency or trust.

Honest, truthful and fair-minded individuals do not see the need to hide any information from any one. Similarly, ethical corporations do not engage in the practices of cooking the books for defrauding the stakeholders. Ethics-based transparency provides two types of benefits: it allows consumers and investors in allocating their resources in an optimal way and governments need not spend any time writing disclosure rules and devoting resources in enforcing them (i.e. it improves efficiency and lowers transaction costs). Rules-based transparency should be considered only as a complement to the ethics-based transparency. Finally, according to both Confucius and Kautilya, creation of ethical environment may be essential to improving the environment. They would have strongly recommended holding conferences in New Delhi or Beijing, like the one just concluded in Paris, on creating ethical environment for solving problem of global warming fairly and quickly.

Article Courtesy: https://www.scirp.org/pdf/TEL_2016012913220025.pdf